2026 Potato Nutrient Schedule

Direct Answer: Apply high-nitrogen fertilizer during vegetative growth, phosphorus-rich amendments at planting for Tuber Initiation, and potassium-dominant formulas during Tuber Bulking to maximize Specific Gravity and prevent watery potatoes. Maintain soil pH between 4.8-5.5 using Elemental Sulfur to suppress Common Scab.

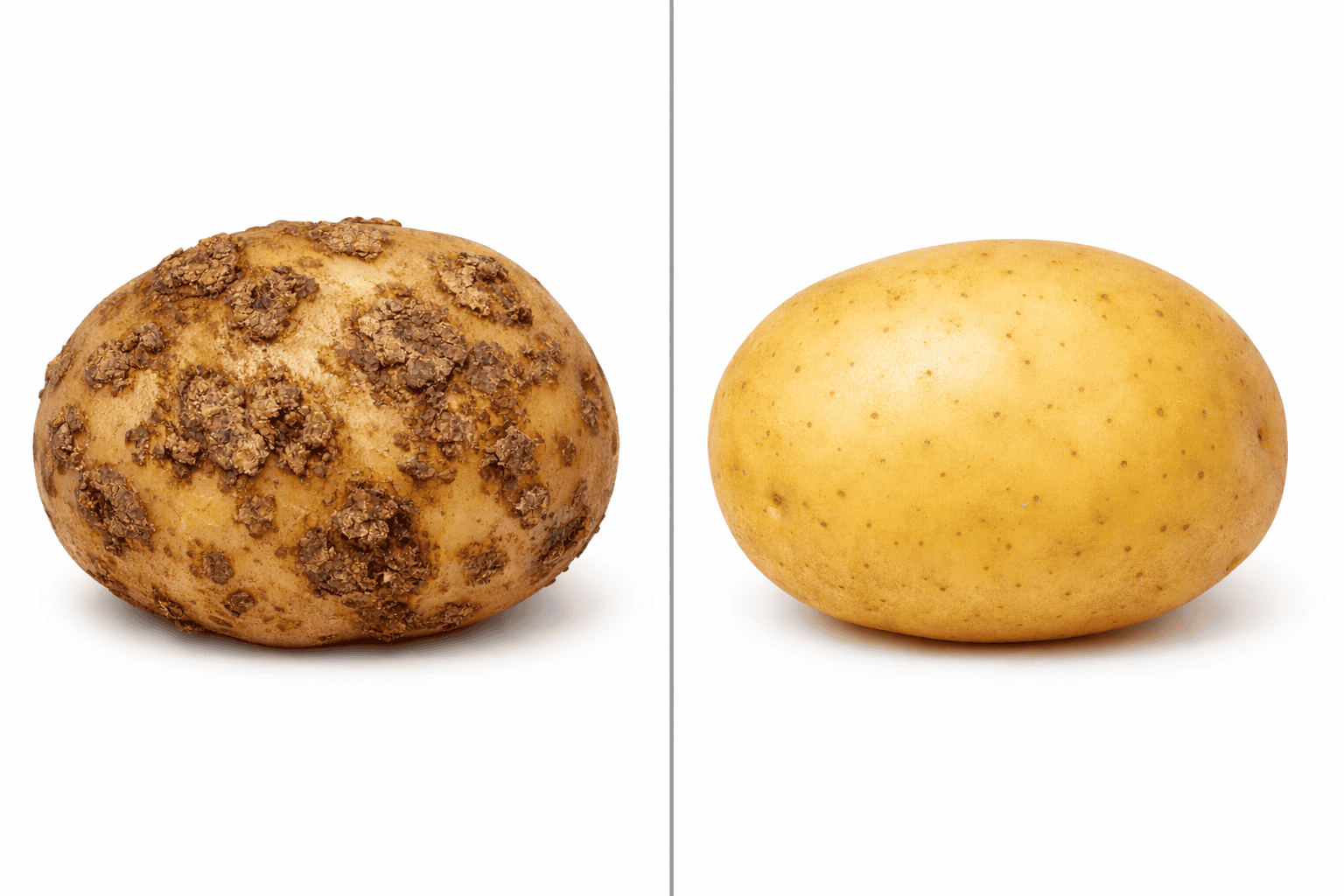

The Scab vs. pH Rule: Why Acidity Determines Marketability

The single most critical factor separating pristine potatoes from blemished, unmarketable tubers is soil pH. When pH rises above 5.5, Streptomyces scabies—the pathogen causing Common Scab—proliferates rapidly. This bacterial disease creates corky lesions on potato skin, reducing both aesthetic appeal and storage quality.

According to Oregon State University Extension research on potato pH management, maintaining acidity between 4.8 and 5.5 creates an environment where scab pathogens cannot establish. Elemental Sulfur applied 4-6 weeks before planting lowers pH effectively. Apply 1–3 pounds per 100 square feet to lower pH by one full point (e.g., from 6.5 to 5.5)

The distinction between scab-prone and scab-free crops often comes down to this single variable. Commercial growers lose millions annually to pH mismanagement.

Understanding Growth Stages and NPK Priority

Stage 1: Sprouting and Vegetative Growth (Weeks 1-4)

While early growth requires Nitrogen, potatoes are sensitive. Use a balanced 10-10-10 starter at planting to establish the canopy without delaying tuber initiation. incorporating fertilizer 2-3 inches below seed pieces.

Nitrogen deficiency at this stage results in stunted plants with pale, yellowing leaves. However, excessive nitrogen延 延 延late in the season delays Tuber Initiation and reduces storage quality.

Stage 2: Tuber Initiation (Weeks 4-6)

High Phosphorus (P) becomes critical when stolons begin “hooking” to form tubers. This underground transformation requires phosphorus for cellular energy transfer and root development. Bone Meal or Rock Phosphate incorporated at planting provides slow-release phosphorus throughout this phase.

University of Idaho Potato Center research demonstrates that phosphorus availability during initiation determines final tuber count. Each plant can produce 5-20 tubers depending on phosphorus adequacy and variety genetics.

The window for maximizing tuber set is narrow. Phosphorus applied after initiation has minimal impact on tuber numbers.

Stage 3: Tuber Bulking (Weeks 6-14)

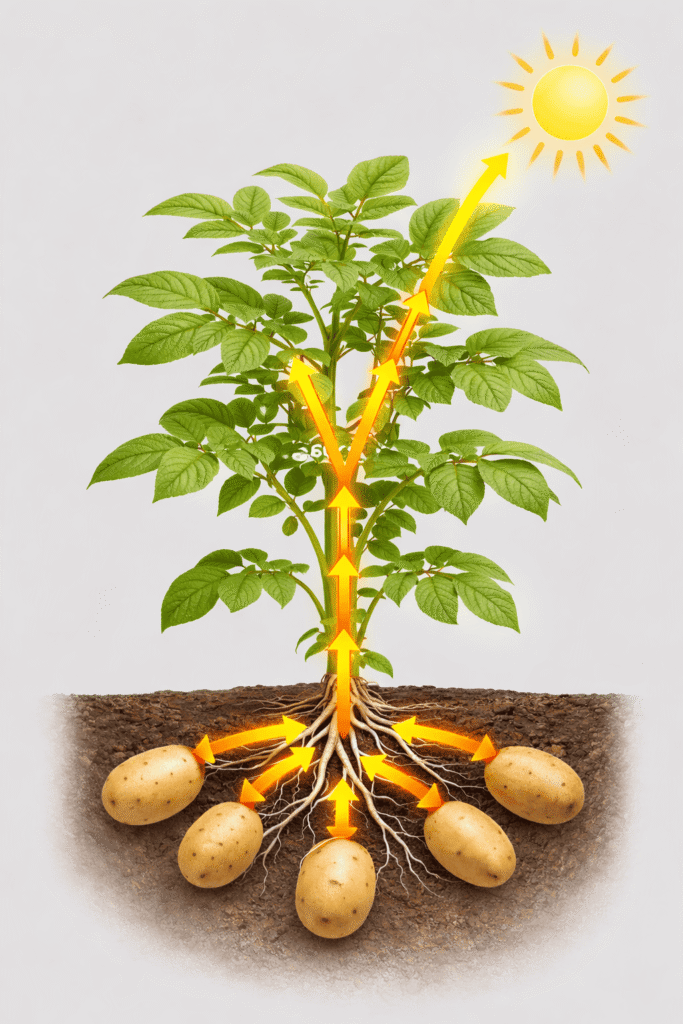

Critical Potassium (K) demand defines the bulking phase. Potassium regulates the enzyme Starch Synthase, which converts photosynthetic sugars into starch within developing tubers. This process, called Starch Translocation, literally pumps carbohydrates from leaves through stolons into tubers.

Low potassium results in watery potatoes with poor Specific Gravity—the industry standard for measuring starch content. Processing potatoes for chips or fries require specific gravity above 1.080, achievable only with adequate potassium.

Apply 5-10-20 NPK ratio during the first hilling operation (week 6-7) and again at second hilling (week 10-11). Side-dress fertilizer 4-6 inches from plant stems to position nutrients in the active root zone.

The Starch Pump: Technical Mechanics of Potassium

Specific Gravity measures the density of potato tubers, directly correlating with starch content and culinary quality. High-starch varieties like Russet Burbank achieve specific gravity of 1.085-1.095 when potassium is adequate.

Potassium functions as the primary cation in Starch Translocation. It maintains turgor pressure in phloem cells, enabling the mass flow of sucrose from leaves to tubers. Without sufficient potassium, photosynthates accumulate in leaves rather than moving to storage organs.

The enzymatic pathway involves potassium-activated Starch Synthase, which polymerizes glucose molecules into amylose and amylopectin. Deficient plants produce tubers with low dry matter content—watery, poor-cooking potatoes that fetch lower market prices.

Sulfate of Potash (K2SO4) is superior to Muriate of Potash (KCl) for potatoes. Chlorine in KCl interferes with starch synthesis, creating waxy texture. The sulfur in K2SO4 provides a secondary benefit by helping maintain proper soil pH.

Potato Fertilizer Comparison 2026

| Fertilizer Type | N-P-K Ratio | Growth Stage | Yield Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-Purpose Starter | 5-10-10 | Sprouting/Vegetative | Establishes canopy, provides balanced foundation |

| Bone Meal | 3-15-0 | Planting (Tuber Initiation) | Increases tuber count by 20-40% |

| Sulfate of Potash | 0-0-50 | Tuber Bulking | Raises Specific Gravity by 0.010-0.015 units |

| Blood Meal | 12-0-0 | Early Vegetative (supplement) | Corrects nitrogen deficiency, deepens leaf color |

| Rock Phosphate | 0-3-0 | Planting (long-term) | Slow-release phosphorus for 2-3 seasons |

| Complete Side-Dress | 5-10-20 | Hilling Operations | Optimizes bulking, prevents potassium deficiency |

Instructional Hilling and Side-Dressing Technique

Hilling serves dual purposes: excluding light from developing tubers (prevents greening) and positioning fertilizer in the active root zone. Proper Side-Dressing during hilling operations delivers nutrients directly where tuber expansion occurs.

First Hilling (Week 6-7)

When plants reach 6-8 inches tall, pull soil from between rows to create 4-6 inch mounds around stems. Apply 5-10-20 fertilizer at 2-3 pounds per 100 feet of row. Broadcast fertilizer 4-6 inches from stem bases before pulling soil.

This positions nutrients in the Tuber Zone—the 6-10 inch radius where stolons and tubers develop. Fertilizer placed directly at stems burns plants; placement too far away remains inaccessible to roots.

Second Hilling (Week 10-11)

Build mounds to 8-10 inches height. Apply additional potassium-dominant fertilizer (0-0-50 or 5-10-20) at the same rate. This second application sustains Tuber Bulking through the final 4-6 weeks of growth.

The hilling operation itself stimulates adventitious root formation along buried stems, expanding nutrient uptake capacity precisely when potassium demand peaks.

Micro-Nutrient Considerations for Large-Canopy Varieties

Magnesium and Manganese are essential for photosynthesis in high-yielding varieties like Russet Burbank and Kennebec. These cultivars produce massive canopies requiring elevated chlorophyll synthesis.

Magnesium deficiency appears as interveinal chlorosis (yellowing between leaf veins) on older leaves. Apply Epsom salt (magnesium sulfate) at 1-2 tablespoons per plant if symptoms appear. The sulfur component simultaneously helps maintain acidic pH.

Manganese deficiency causes similar symptoms on younger leaves. Foliar spray with manganese sulfate (1 tablespoon per gallon) corrects deficiencies within 7-10 days. Soil applications are less effective because manganese availability decreases in alkaline conditions.

Anti-Alkaline Amendments: Maintaining Scab-Free Conditions

Beyond Elemental Sulfur, several amendments help maintain the 4.8-5.5 pH target:

Avoid Wood Ash: Despite recommendations in general gardening contexts, wood ash is alkaline (pH 9-13) and directly raises soil pH. A single ash application can push potato beds into the scab-prone zone above 5.5.

Peat Moss: Incorporating 2-3 inches of sphagnum peat moss lowers pH and improves soil structure. Peat is naturally acidic (pH 3.5-4.5) and provides organic matter without alkalinity risk.

Sulfur-Coated Urea: For nitrogen supplementation during vegetative growth, sulfur-coated urea releases nitrogen slowly while acidifying soil. This dual-action fertilizer prevents the pH creep that occurs with conventional nitrogen sources.

Monitor pH every 3-4 weeks during the growing season. University of Idaho research demonstrates that pH can shift 0.3-0.5 units during active growth, especially with heavy irrigation or rainfall.

For a step-by-step technical guide on how to lower soil pH effectively, refer to our acidification protocol

Common Fertilization Mistakes and Corrections

Mistake 1: Using Tomato Fertilizer

Tomato formulas (typically 5-10-5 or 4-7-10) contain insufficient potassium for potatoes. While both crops are Solanaceae family members, their nutrient demands differ dramatically. Tomatoes prioritize fruit production with moderate potassium; potatoes require extreme potassium for Tuber Bulking.

Furthermore, many tomato fertilizers contain high levels of Calcium, which, while great for tomatoes, can actually raise soil pH and increase the risk of Common Scab in potatoes.

Using tomato fertilizer results in small, watery tubers with poor storage quality.

Mistake 2: Applying High-Nitrogen Fertilizer During Bulking

Continuing high-nitrogen applications past week 6 delays tuber maturation and reduces Specific Gravity. Late-season nitrogen promotes continued vegetative growth at the expense of starch accumulation.

Growers targeting early harvest can tolerate slightly higher nitrogen. Those growing for storage must minimize nitrogen after Tuber Initiation.

If your plants are already showing signs of yellowing lower leaves, they may be suffering from a different issue—see our guide on How to Fix Nitrogen Deficiency in Plants

Mistake 3: Surface Application of Potassium

Potassium is relatively immobile in soil. Broadcasting potassium fertilizer on the soil surface leaves it stranded 4-6 inches above the active root zone. Side-Dressing during hilling operations is mandatory for efficient potassium delivery.

Harvest Timing and Late-Season Nutrition

Cease all fertilization 4 weeks before planned harvest. This allows tubers to develop proper skin set and maximizes storage potential. Late fertilization, especially nitrogen, results in weak skins prone to damage during harvest and storage.

Specific Gravity continues increasing during the final 2-3 weeks even without additional fertilizer, as existing potassium reserves complete Starch Translocation. Early harvest sacrifices 15-25% of potential yield as tubers bulk rapidly during the final growth period.

Monitor foliage condition: when 50% of leaves yellow naturally, tubers have reached physiological maturity. Digging 2-3 weeks after this point maximizes both yield and storability.

Regional Adaptation: University-Sourced Protocols

The University of Idaho Potato Center provides region-specific nutrient management protocols accounting for soil type, irrigation method, and variety selection. Sandy soils require more frequent potassium applications (3-4 times vs. 2 times in loam soils) due to leaching.

Oregon State University Extension emphasizes the connection between irrigation water quality and pH management. Alkaline irrigation water (pH 7.5-8.5) requires doubled Elemental Sulfur applications to maintain the scab-suppressing 4.8-5.5 range.

These institutional resources represent decades of field research conducted on thousands of acres. Home growers and commercial operations alike benefit from adapting these evidence-based protocols.

Authority Citations:

- University of Idaho Potato Center: Potato Nutrient Management Guidelines

- Oregon State University Extension: Managing Soil pH for Potatoes

For growers seeking maximum yield and marketable quality, the 2026 protocol emphasizes three core principles: acidic pH maintenance through Elemental Sulfur, stage-matched NPK ratios prioritizing potassium during Tuber Bulking, and precision Side-Dressing during hilling operations. Following this science-based framework produces tubers with optimal Specific Gravity, minimal Common Scab, and superior storage characteristics.